Soil erosion is an ongoing threat to multiple industries today. Once soil erodes, it becomes difficult to restore that land area to its former production levels. With some simple soil erosion prevention methods in place, it is possible to control or even prevent common forms of the erosive process. Here are the most common methods and why they are able to help stop erosion.

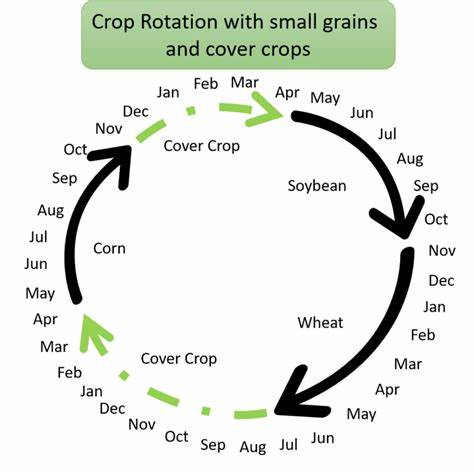

Rotating crops through different fields is more than planting corn one year and soybeans the next. Planting croplands in a series of strips for crops and then hay or clover will help to further stabilize the soil and prevent water run-off. This is why you will see some farms growing corn and hay in the same field with the same irrigation system.

What Is Crop Rotation?

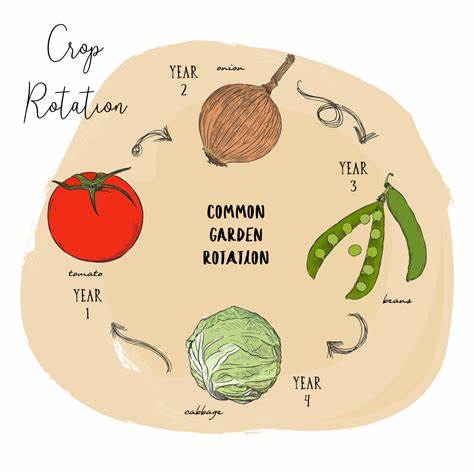

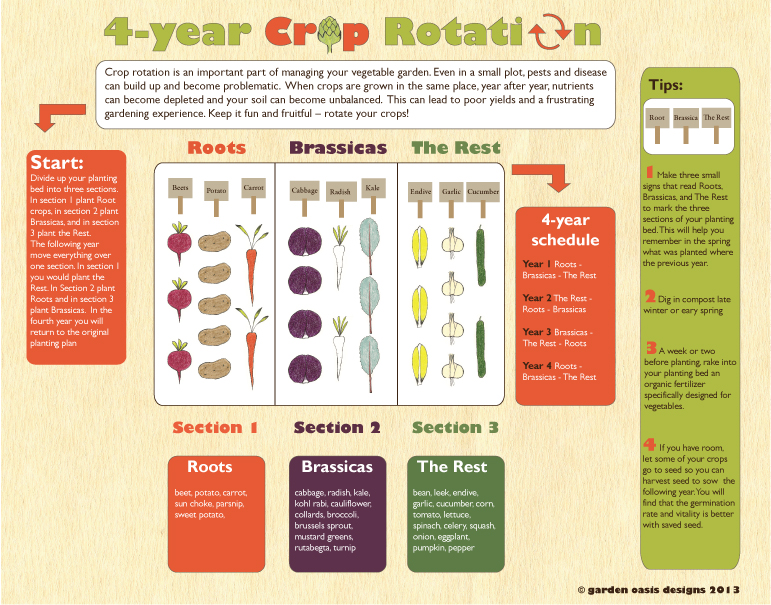

The concept of crop rotation is simple: It’s the practice of not planting the same crops in the same place in back-to-back years. By not planting the exact same vegetables in the exact same spot every year, you can avoid having pests and diseases continuously build up in the soil. If you move the crop, the pest or disease has no host on which to live. Ideally, rotate a vegetable (or vegetable family) so that it grows in a particular place once out of every 3 to 4 years.

For example, if you planted tomatoes in the same garden bed year after year, they’re more likely to be hit by the same pests or diseases that affected your tomato crop last year. So you’d want to plant them in a different bed in the following year. Then, in that first bed, you’d plant a different sort of crop such as carrots, broccoli, or chard. Finally, in the third year, you could plant tomatoes in their original spot again.

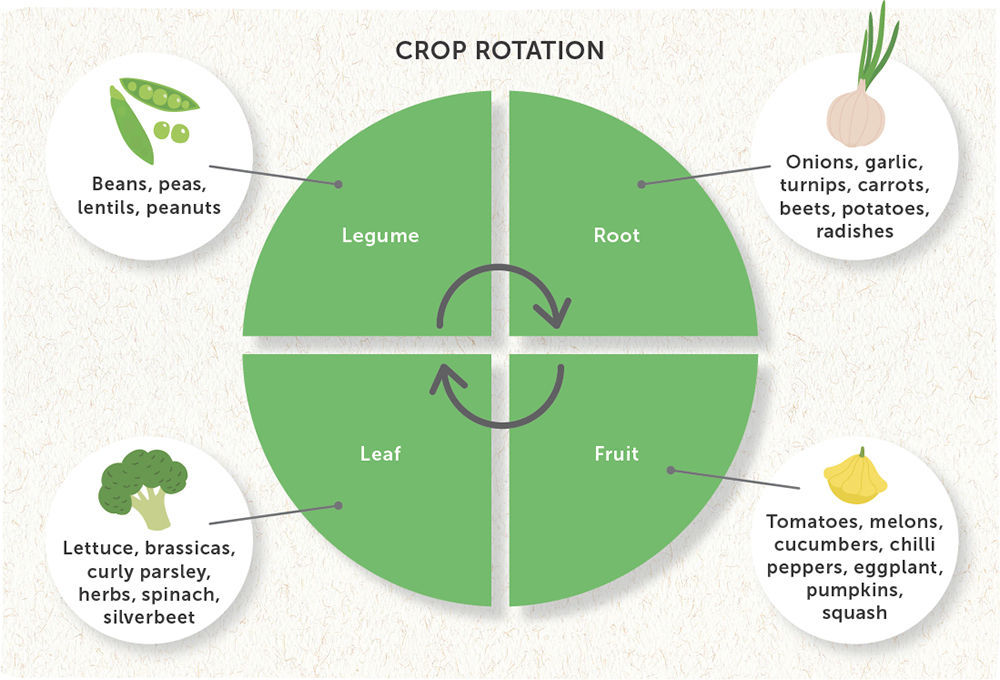

The purpose of crop rotation is not only to avoid pest problems, but also to consider the soil health and the nutrients that different plants need from the soil.

Get to the Root of Crop Rotation

Crop rotation also benefits the health of the soil, structurally speaking. Plants with different root lengths benefit the soil by aerating it in different ways. Deeply rooted crops such as tomatoes, carrots, or beets break up the soil, creating channels for air and water as they seek out minerals in the subsoil, bringing them closer to the surface where other plants can use them next year.

Planning Crop Rotation in Your Garden

Depending on the size of your garden, you can plan rotations that cover 3, 4, 5, 6, or more years, with 3 years being the minimum recommended.

As noted above, the best way to rotate annual vegetables is to group them by their plant family, since they are susceptible to the same pests and diseases and also have similar maintenance requirements. For instance, all plants in the cabbage family are best grown together, as this makes it easier to net them against cabbage moths and birds—and there’s no risk of accidentally passing on crop-specific soil-dwelling pests and diseases to the next crop.

A handy way to set crop order is to give each plant family a shade relating to the colors of the rainbow, as shown below. Using this order of rotation is optional, but it helps to make sure that the soil is in the correct condition for the following crop.

- Working from the inside of the rainbow out, you can see which plants belong together and which should come next in each bed. The rotation starts with lilacs and blues—onion family plants and peas/beans—which are commonly grown together as they both like soil enriched with compost and take up little space. Once you’ve harvested your onions and leeks from your first bed, the next crop in that spot would be cabbages, cauliflower, broccoli, and so on, for the first seven categories.

- Plants in the Miscellaneous (grey) category are useful for plugging gaps in your beds, as they don’t tend to suffer badly from particular soil-borne pests and diseases, and can be fit in anywhere you have room, although it’s still a good idea to move them around from year to year as much as possible (particularly sweet corn, which can suffer from rootworm).

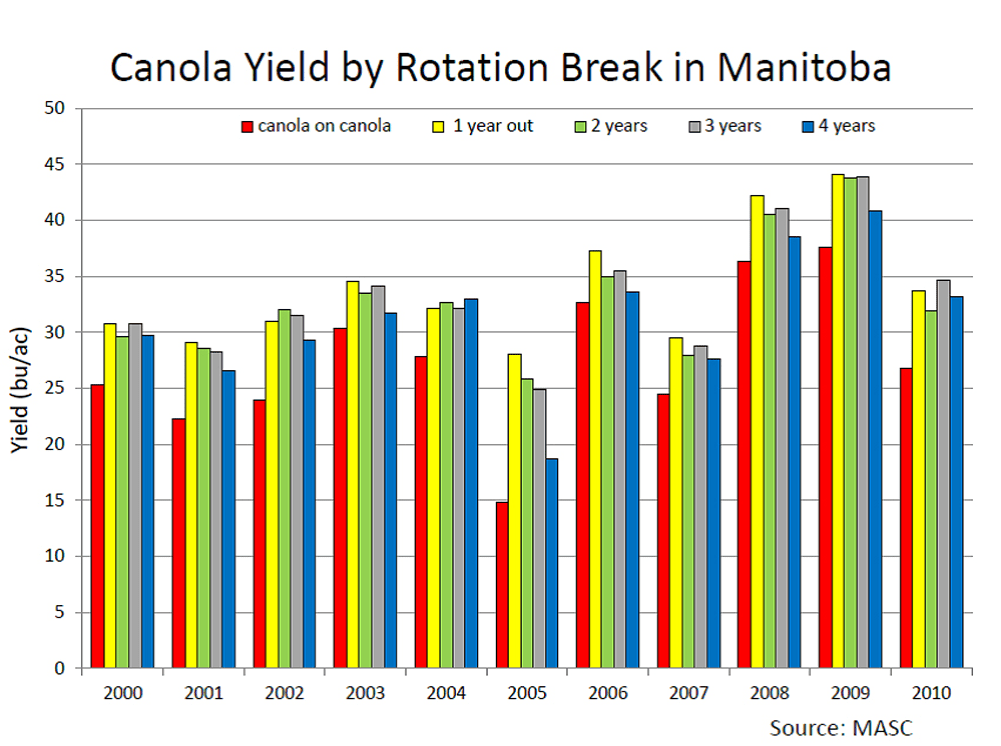

Farm profitability from grain production is an age-old concern of farmers. Improving yield stability is also an important management strategy to counteract weather extremes (i.e., heat waves, droughts, flooding) that stress both crop growth and farm profitability. Farmers need reliable information about the effectiveness of crop rotation and fertilizer management that involves many years of data to account for the year-to-year variability in growing conditions.

Here, we share the results from a long-term rainfed no-till crop rotation and nitrogen (N) fertilizer systems study conducted by the USDA Agricultural Research Service at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln’s Eastern Nebraska Research and Extension Center (ENREC) (Table 1). While producers typically increase fertilizer amounts for continuous crops, fertilizer inputs were determined by the crop phase present during the year of application to maintain experimental uniformity.

| Treatment | Year Started | Description | Abbreviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crop rotation | 1972 | Continuous corn | CC |

| Continuous soybean | SS | ||

| Continuous grain sorghum | GG | ||

| Corn – soybean | CS | ||

| Grain sorghum – soybean | GS | ||

| Corn – soybean – grain sorghum – oat/clover2 | CSGO | ||

| Corn – oat/clover – grain sorghum – soybean | COGS | ||

| Nitrogen rate3 | 1982 | No N (0 lb N/ac) | 0N |

| Low N (80 lb N/ac for C, G; 30 lb N/ac for S) | Low N | ||

| High N (160 lb N/ac for C, G; 60 lb N/ac for S) | High N |

More diverse rotations improve yield and yield stability.

- Under no fertilization (0N), yield for corn or grain sorghum rotated with soybean was similar to grain yield in fertilized continuous cropping systems (Figure 1).

- Compared to continuous cropping, fertilized corn yield improved 29% and fertilized grain sorghum yield improved 20% when grown in two-year rotations, and up to 48% (corn) and 29% (grain sorghum) when grown in four-year rotations that included a legume winter cover crop in just one of four of those years (Figure 1).

- Soybean yield was stable regardless of N application and tended to improve with rotation complexity (Figure 1).

- Rotating crops increased long-term yield stability and decreased crop losses during drought by 14-90% compared to continuous cropping.

Soil erosion is a very real threat to our planet today. More than half of our top soil has disappeared over the last century. By limiting the impact of erosion, we can continue to benefit from the presence of stable soil for years to come.

- Specific Measure Erosion Soil ofspecific measure erosion soil erosion soil pollution specific measure tackle engineering measure erosion silt fish-scale effective erosion measure solution erosion soil to solution erosion soil the maesures erosion soil salinization solutions soil of salinization treatment soil of